Estate Settlement

May 01, 2025

What to Do When Someone Dies in California

Follow this step-by-step guide to navigate legal duties, probate, and estate tasks with clarity and confidence.

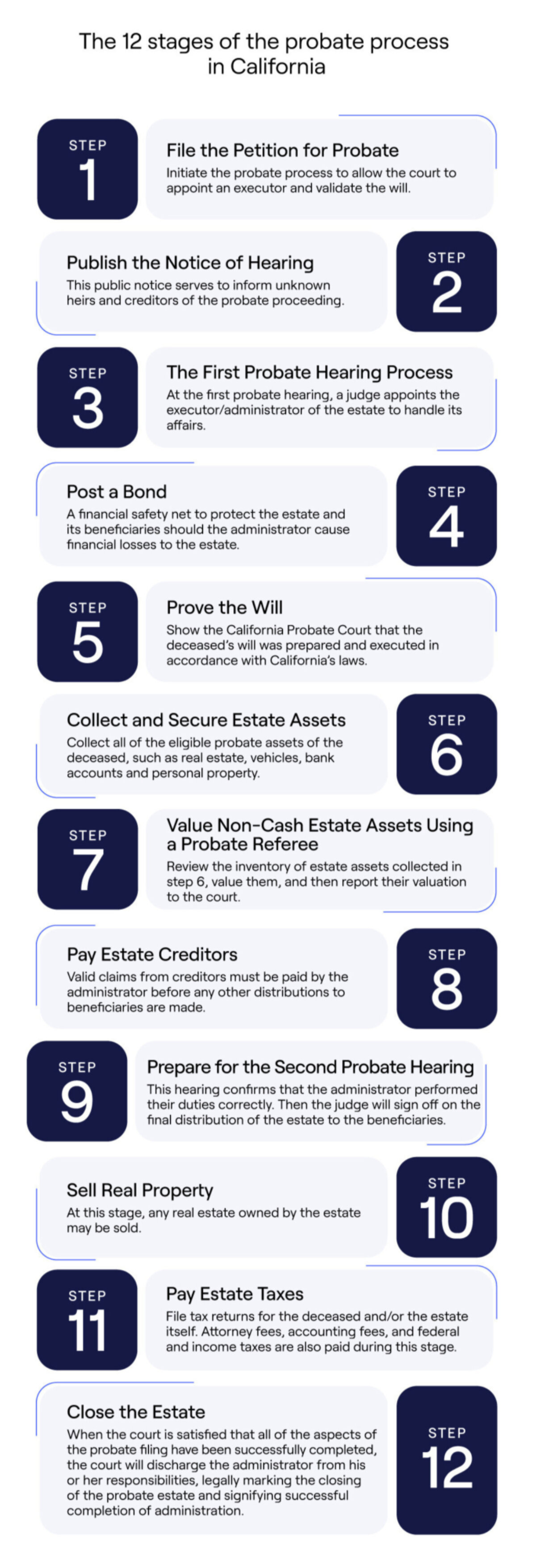

The probate process in California can be confusing and lengthy; we've laid it out for you in an easy 12-stage process. Read on to know what steps to follow.

The passing of a loved one or friend is a time filled with unexplainable grief. It can also be filled with deep legal responsibility if you have been named the executor or administrator of their estate—the person authorized to manage their affairs after they have passed. One part of this process includes distributing assets to their intended heirs.

When someone dies in California the administrator is required to go through the probate process in California through the California Probate Court system. Before any assets or real estate can be distributed to the beneficiaries, a number of specific steps must be completed in a certain timeframe and order. To help you manage your legal duties as an executor or administrator, we’ve outlined the 12 stages of California’s probate process below and what you can expect at each juncture.

Probate is a legal process defined under California law that transfers the estate’s title to property and/or assets to the beneficiaries of the decedent. It is a court-supervised transaction that involves filing a petition for probate, a hearing, appointing an administrator or executor of the estate, proving the will was legitimate, potentially posting bond and other complex steps. Note that probate may need to take place whether there was a will in place or not.

As California probate is a complex process, it also comes with substantial probate fees. Effective 2025, statutory fees for executors/administrators and attorneys are set at the following amounts:

4% on the first $100,000 of the estate’s gross value

3% on the next $100,000 of the estate’s gross value

2% on the next $800,000 of the estate’s gross value

1% on the next $9,000,000 of the estate’s gross value

0.5% on the next $15,000,000 of the estate’s gross value

On top of paying the parties that help administer the estate, California courts also charge a number of filing fees. For example, filing a petition for letters testamentary or letters of administration generally costs $435—a fee amount common across multiple filing types. Keep in mind that each county court may have their own specific filing fees.

Typically, the probate procedure in California goes through a series of 12 stages, though the exact process may differ depending on the county you file in. Even though the process may change slightly, the time to complete probate in California generally takes anywhere from several months to a couple of years to complete depending on the complexity of the estate and the courts’ availability.

Keep in mind that California law requires a status report or final accounting procedures to be filed within 12 months of the administrator’s appointment. If a federal estate tax return is required, this timeline is extended to 18 months.

Here's a summary of the 12 steps. They are also explained in detail in this blog.

To file a petition for probate in California, you must submit the petition for probate ( Form DE-111), with the original will attached, to the court in the county where the decedent resided immediately before their death. This is the first step in initiating the probate process, allowing the court to appoint an executor and validate the will.

If the decedent died without a will—known as being intestate—then the party making the filing must have priority to be appointed as an administrator. Someone with priority to administer an estate is typically a spouse or registered domestic partner, adult child, grandchild, great-grandchild, parent, sibling, niece/nephew or grandparents, in that order.

After filing California Form DE-111, the county court will be notified that a hearing needs to be scheduled, which may be held within a few months’ time or much more, depending on the court’s availability. You will be required to provide the courts with the will, proof of service and any other formal documentation they require.

Following the initial petition for probate filing and once a hearing date is set, a Notice of Hearing is published in a local newspaper once a week for three consecutive weeks. This public notice serves to inform unknown heirs and creditors of the probate proceeding.

Additionally, a copy of the notice must be mailed to all parties named in the will (if one exists), as well as all known heirs. The mailed notice must be sent at least 15 days before the hearing date, while the publication must start at least 20 days before the hearing.

At the first probate hearing a judge appoints the executor/administrator of the estate to handle its affairs. Most often this is the person named in the will of the deceased, though you may suggest who you believe the administrator should be in the probate petition.

If there is no will, or if the named executor cannot or chooses to not act for the estate, then the judge will appoint someone based on an order of priority. This person most likely will be a spouse or closest living relative such as child, grandchild, parent or sibling.

In some cases, the Probate Courts require the administrator/executor of an estate to post a Calfironia probate bond. This is a guarantee purchased from an authorized bond company as a way to protect the estate and its beneficiaries should the administrator cause financial losses to the estate. Think of it as a

California Probate Courts typically require an administrator to be bonded to ensure that they execute their fiduciary responsibilities properly and completely. If the administrator lives outside California, a bond will be required. This is true even if the will stipulates for a bond to be waived.

Bond prices are based on several factors, most importantly the amount that the court requires, as well as the administrator’s creditworthiness. A reduction in the amount of the bond may be requested if the court can be assured that a large amount of the estate is secured by a savings account that is not subject to outstanding liens—and that it can only be accessed by a court order.

In some cases the need for a bond may be waived. For instance, the will of the deceased may contain a bond waiver clause, a paragraph stating a surety bond is not required. Additionally, all the beneficiaries can sign waivers of bond (California Form DE-111(A-3e)) waiving the need for bond. That said, any potential waiving of bond requirements is subject to a judge’s discretion.financial safety net.

Proving the will to a judge in California’s Probate Court means showing that the deceased’s will was prepared and executed in accordance with California’s laws. This means, at a minimum, that the adult who signed the will had capacity to do so and was not acting under undue influence or duress.

In addition to the testator being in proper condition, a valid will is also signed in the presence of two or more witnesses who are not beneficiaries to the will. An exception to this is made for holographic or “handwritten” wills, however. Proving a handwritten will requires the testimony of at least one witness who personally knew the testator and has knowledge of their handwriting. A holographic will may be proven through testimony or other evidence verifying that the signature and material portions of the document are in the testator’s handwriting.

A pre-printed “fill-in-the-blanks” will (statutory will) is another type of document that can be valid before a court. So long as the statutory will was developed in accordance with California law and signed in front of at least two witnesses that—again—are not beneficiaries.

Probate Fact:

In California, a will is considered “self-proving” if it meets all legal requirements for validity, is not holographic, and includes a declaration by the witnesses made under penalty of perjury. A self-proving will may eliminate the need to locate and call witnesses during the probate process.

As the estate administrator, one of your most important responsibilities is to collect all of the eligible probate assets of the deceased. To change the ownership of an asset held in the name of the deceased, the administrator needs to transfer title by by obtaining a certified copy of the death certificate and Letters of Administration or Letters Testamentary from the probate court, and presenting them to the relevant party (e.g., bank, DMV, title company).

The personal representative must complete and file Form DE-160 (Inventory and Appraisal) and DE-161 (Attachment). Cash-type assets may be appraised by the representative, while all other assets must be appraised by a court-appointed Probate Referee.

Probate assets generally include property titled solely in the decedent’s name, such as real estate, vehicles, bank and brokerage accounts, stocks, and personal property. Once filed, the Inventory and Appraisal becomes part of the public record.

Non-probate assets, such as those in a living trust, retirement accounts with named beneficiaries, and pay-on-death (POD) or transfer-on-death (TOD) accounts, usually bypass probate. If a beneficiary predeceased the decedent and no alternate was named, that asset may revert to the estate and require probate.

The administrator is responsible for filing California Form DE-160 and it is the court’s responsibility to assign someone to value non-cash assets. This person is known as a probate referee.

Probate referees can perform reliable and prompt appraisals of all types of estate assets, including real property and recreational vehicles. They must pass a state-approved test to become licensed and complete 15 hours of continuing education annually.

Their primary duty is to review the inventory of the estate assets collected in step 6, value these assets and then report their valuation to the court. To perform a complete valuation, the referee gathers information about the estate’s assets from the administrator, evaluates each based on market data, and reports fair market values to the court.

Key Detail:

Under California law, a probate referee’s fees are 1/10th of one percent (0.1%) of the estate’s appraised assets’ value, which equals $1 of fees for every $1,000 of appraised value. So an estate with appraised property valued at $500,000 would incur $500 in probate referee fees. Their fees are paid out from the estate.

As part of the overall probate process, the administrator provides notice of the deceased’s passing by mailing Form DE-157, (Notice of Administration to Creditors) to any known creditors. Following receipt of this notice, creditors can submit a claim against the estate. Valid claims must be paid by the administrator before any other distributions to beneficiaries are made. This may include any other necessary liabilities.

Under California law, creditor claims must be filed with the court and a copy must be delivered to the personal representative within the later of:

Four months after the court issues Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration, or

Sixty (60) days after the mailing or personal delivery of Form DE-157.

If all has gone well so far, the second probate hearing should be less intensive than the first. At this hearing, the judge confirms that all known creditors have been paid and that the administrator performed their duties correctly. Part of the administrator’s duties includes filing an accounting and a petition for final distribution showing the:

Assets collected

Debts paid

Proposed distributions to beneficiaries

The court reviews this accounting and petition filing for approval before authorizing final distribution.

If all the above is confirmed, the judge will sign off on the final distribution of the estate to the beneficiaries.

At this stage, any real estate owned by the estate may be sold. If the administrator does not have full authority to do so under the Independent Administration of Estate Act (IAEA)---or the court requires confirmation—they must file Form DE-260, (Report of Sale and Petition for Order Confirming Sale of Real Property). However, if the administrator has full IAEA authority and no objections have been raised, the sale of real property may proceed without court approval.

Remember that any real property to be sold also should have been listed on California Form DE-160 during step six of the probate process.

When it comes time to sell the real property of the deceased, the process can be complicated or simple depending on the authority the administrator is given by the court.

If an administrator has been given full authority under the IAEA, laid out in Probate Code §10500 to §10538, they can sell real property as they see fit. There are some stipulations in regard to the deceased’s principal residence, however. If an administrator is only given partial authority under the IAEA, then selling real property is much more complex. For starters, they must publish a notice in a local newspaper where the deceased resided. Following that they can then accept an offer on the property and then file California Form DE-260. Finally, the administrator must attend a court hearing during which overbidding may occur. Bidders can submit higher offers during the hearing in an auction-like setting and the court confirms the highest qualified bid.

As an administrator or executor, there is a high chance you will need to file at least one tax return as administrator. You may need to file tax returns for the deceased and/or the estate itself. Attorney fees, accounting fees, and federal and income taxes are also paid during this stage.

If you need help , we've created a California probate fee calculator to help you understand the attorney fees and executor compensation.

It is important that the estate taxes are paid on time, as the estate administrator may be held liable for not filing tax returns on time, or mismanaging estate assets. The court may decide to impose personal liability on the estate administrator if they feel they have neglected this aspect of probate.

Important to note for executors:

Executors are entitled to reasonable compensation for fulfilling their duty as an estate administrator, however it is important to note that the executors compensation is taxable income and must be filed as such on your federal income tax return.

The final step of the California probate process is when the administrator provides a complete and final accounting of all the steps they have taken to administer the estate. The required petition that is filed as the concluding action of the Administrator will summarize all the actions made on behalf of the estate.

A hearing is also scheduled for the report to be presented to the judge, who will in turn review if the administrator has handled everything correctly and undergone careful accounting. The court will generally require supporting documentation, such as receipts, to confirm that all distributions have been made appropriately. When they are satisfied that all of the aspects of the probate filing have been successfully completed, the court will "discharge" the administrator from his or her responsibilities. This step legally marks the closing of the probate estate, signifying successful completion of administration.

Any appeal to the judgment must be filed within 60 days of the mailing or personal service of the entry of judgment.

There’s a lot of steps to keep track of in the probate process. Below is a table outlining the key steps that occur and an expected timeframe for each. Note that the timeline for probating an estate varies greatly depending on the court’s schedules and the complexity of the estate being probated. Use this chart only as a general guideline, not a hard and fast rule.

Stage Name | Summary of Stage | Estimated Timeline |

File Petition for Probate | Executor/administrator Form DE-111 and related documents with the county probate court to begin the case. | 2–4 weeks |

Court Issues Hearing Date & Notice is Published | Court schedules a probate hearing weeks or months out depending on availability. Notice of hearing must be published 3 times in a local newspaper and mailed to heirs/beneficiaries. | 3–8 weeks (varies depending on court schedule) |

Initial Probate Hearing, Appointment of Executor/Administrator and Posting Bond | Court formally appoints the executor or administrator. The personal representative may be required to post bond. If bond is required, this step may be delayed. | 2–4 weeks (varies depending if bond is required) |

Prove the Will (if applicable) | Court verifies the validity of the will (may require witness declarations or affidavits). | 1–2 weeks |

Collect & Secure Assets | Executor/administrator gathers bank accounts, property titles, investments, and personal property belonging to the decedent. | 1-3 months |

Inventory & Appraisal of Assets | Executor/administrator files Inventory and Appraisal (Form DE-160) with the court. A probate referee may be required to appraise non-cash assets. | 1-4 months |

Notify & Pay Creditors | Executor/administrator publishes and sends Notice to Creditors (Form DE-157). Creditors have up to four months to file claims. Executor reviews, approves, or rejects claims and pays valid debts. | 1-3 months |

Pay Taxes & Other Obligations | Executor/administrator completes the decedent’s final income tax return and any estate taxes due. Pay funeral expenses, administrative costs, and legal fees. | 1-2 months (often overlaps with former step) |

Sell Real Property (if applicable) | Executor/administrator may sell estate property (home, land, etc.) with court approval or under Independent Administration authority. | 2-4 months (variable; may overlap with prior steps) |

Prepare Final Accounting & Petition for Distribution | Executor/administrator completes final accounting showing receipts, payments, and proposed distributions. Then they petition for final distribution and schedule a closing hearing. | 1-2 months |

Final Hearing & Distribution | Court reviews and approves the final accounting. Assets are distributed to heirs/beneficiaries. The executor/administrator is discharged, and the estate is closed. | 2–3 weeks |

The California probate process is lengthy, time-consuming, complicated and court-supervised. Not only will you have to juggle the role of griever, family member, friend and estate administrator, but also have judges double-checking your decisions.

Sound overwhelming? There’s a solution. Our team of estate experts is made up of leaders in probate law and accounting professionals providing estate settlement services in California.

Not sure you need that much assistance? You can download our complete, 12-step blueprint to probating an estate in California instead.

Simplify Probate Today

Simplify Probate Today

Get expert guidance from our specialists who've helped 10,000+ families.

Book a free consultation